We often associate “eviction” with displacement and removal, boxes and furniture thrown to the curb. When a landlord files to evict a tenant—whether for nonpayment of rent or for property damage—we assume they do so to move them out. As we show in a new article published in the journal Social Forces, that assumption turns out to be missing half the picture. While some landlords do file intending to remove tenants, others use eviction filings as a way to collect rent and additional fees. That results in the phenomenon of serial eviction filings. This article offers the most comprehensive analysis to date of its prevalence across the United States.

Click Here To See Our Latest Research in Social Forces

In assembling the Eviction Lab’s national database of evictions, we observed an unexpected pattern: the same landlords repeatedly filed for eviction against the same individuals at the same addresses across multiple months, sometimes even years. Landlord Ben Jones filed against John Smith of 123 Main Street in June and then—in an entirely separate case—filed against John again at the same address in November. What was going on? In this article we examine why, where, and how frequently landlords file serially for eviction.

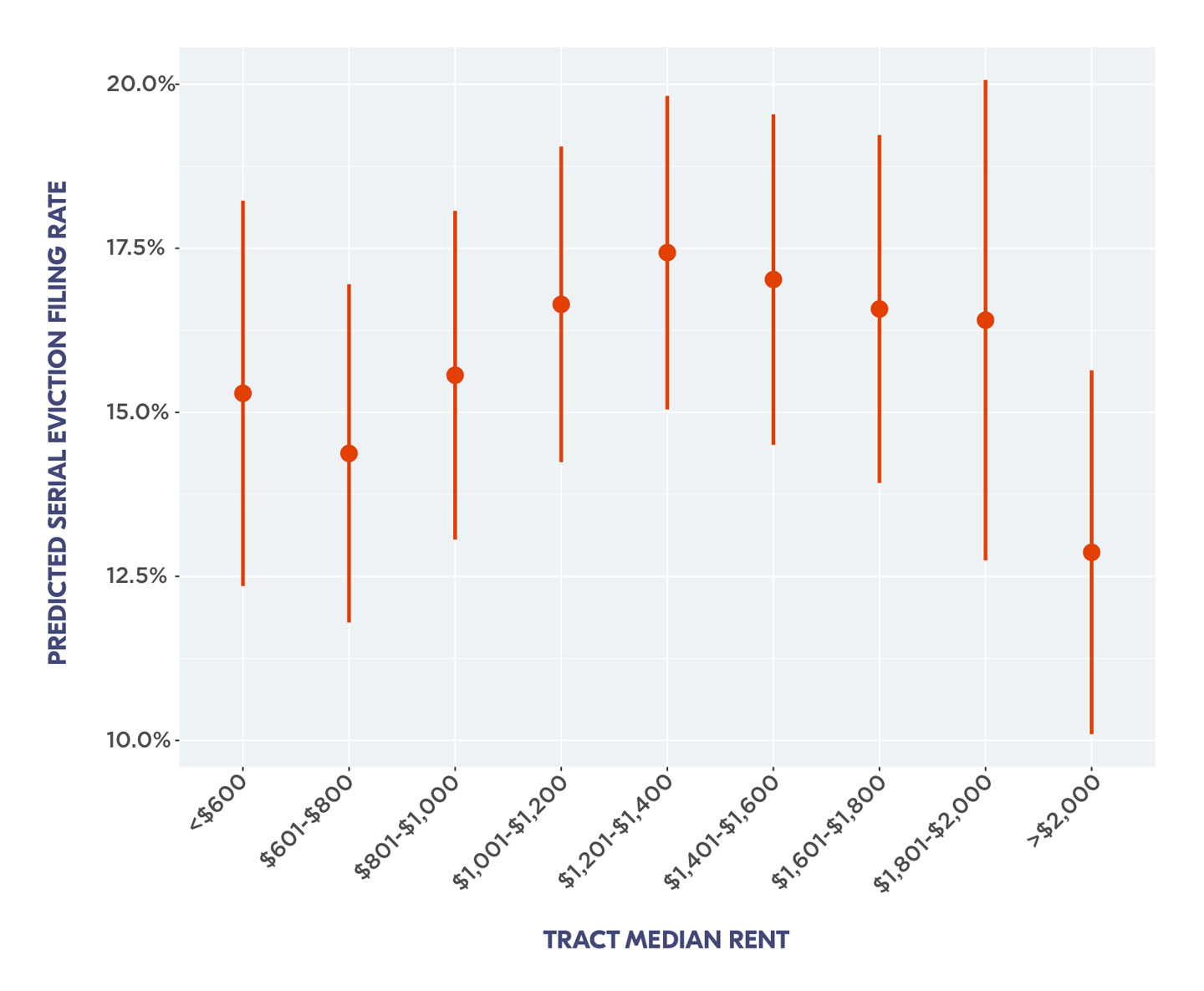

What we initially thought might be errors in the data turned out to be a common and devastating reality for many households. We found that nearly one-third of households facing eviction in 2014 were filed against repeatedly at the same address. In the article, we show that eviction is often a drawn-out process that repeatedly affects households. We also show that these serial eviction filings were more common in mid-range rental markets—areas with rents between $1,200 and $2,000 per month—and in counties that made the legal process of eviction fast and cheap.

This figure shows the distribution of predicted serial eviction filing rates by neighborhood (Census tract) median rent, controlling for other neighborhood characteristics. Dots represent point estimates, and red vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Court records allow us to look at where and how frequently serial eviction filings took place. To understand why they occurred, we interviewed 43 property managers, attorneys, and court officials in two socio-demographically similar cities with very different serial eviction filing rates: Charleston, South Carolina and Mobile, Alabama.

The interviews showed how property managers use the courts to collect rent and late fees, while passing legal costs onto tenants. Serial eviction filings were common in Charleston. Property managers we spoke with there knew that tenants could usually make rent even after an eviction was filed, yet repeatedly filed eviction cases to collect rent and additional fees. By contrast, serial eviction filings were rare in Mobile, where eviction filings were more expensive and often served as a last resort to remove a tenant.

Even if they are not displaced, serial eviction filings have serious consequences for tenants. Informed by the interviews, we attempted to show how much tenants facing eviction have to pay, above and beyond rent, to stay in their homes. We estimated that each eviction filing translates into approximately $180 in fines and fees for the typical renter household, raising their monthly housing cost by 20%. Multiple eviction filings also tarnish their rental history, creating additional barriers to future moves.

Our findings have important policy implications.

First, municipalities could potentially reduce serial eviction filing by increasing filing fees or making the eviction process more time-consuming for landlords. In many parts of the country, landlord-tenant courts are being used to facilitate routine rent collection. That does not need to be the case. Slower moving, more expensive eviction processes could result in fewer tenants facing serial eviction filings.

Second, policy makers can and should regulate the fines and fees that property managers collect through serial eviction filing. Washington, D.C. and Massachusetts have already begun to do so, and other states or counties could pursue these strategies.

Third, rent payment and pay schedules should be more closely aligned. According to the U.S. Census, only 5.4% of private businesses in the U.S. pay their employees on a monthly basis; the remainder pay workers on a semimonthly (18.6%), biweekly (42.2%), or weekly (33.8%) basis. Serial eviction filings are often the result of mismatches between these pay schedules and strict monthly rent deadlines. These deadlines are institutional holdovers from a bygone era. They should be adjusted to reflect contemporary pay schedules.