The COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult for hundreds of thousands of people to pay rent and stay housed. At the Eviction Lab, we believe that everyone deserves a place to call home, especially during an emergency like this.

The following is a guide with some of the most relevant questions that tenants could have as the eviction protections lapse. We are encouraging everyone to learn about your rights in court, search for legal counsel and apply to rental assistance if it is available.

This page was updated on January 20th, 2022.

Note: this page is intended to provide general information and does not constitute legal advice. Please consult an attorney barred in your state for advice about a specific legal matter.

The federal moratorium on evictions was struck down by the Supreme Court in August of 2021. but local moratoriums remain active in some cities and states. Some local moratoriums remained active afterwards in specific cities and states, but most have expired by now.

Across the country, renters have a constitutional right to due process, which means they have the right to be heard and can dispute an eviction in court. Although it is not common, in some specific places, tenants might have to post a bond–pay the rent that they owe to an account held by the court system–to get a hearing. Specific locations may still have other protections, but how they can help you and how to apply for these varies from place to place. This is why it is important to reach out to local experts.

Contact local housing advocates and legal aid organizations in your city or state to learn your rights, seek legal counsel and find the most up to date information. More legal aid providers can be found through state bar associations (associations of all attorneys in the state) and NAIP. More legal assistance can be found from the American Bar Association and LawHelp.org. Find or post resources in your community to our sister website Just Shelter.

Many rental assistance programs have expired, but some jurisdictions have received new funds or have allocated more money for rental assistance. Check with local governments and local housing organizations to find out if there’s still help where you live. You can also call 2-1-1 to learn more about how to apply for the rental assistance available in your area.

Depending on where you live, these programs might be managed by a city, a county, a state or a non-profit. You can find hundreds of rental assistance programs available in this list.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has created a tool where tenants and landlords can search for the available programs by locality: www.consumerfinance.gov/renthelp.

Apply for rental assistance as quickly as you can. If your landlord files to evict you while you are waiting to hear back about your application, be sure to let the court know that you have an application pending.

Depending on the program in your area, your landlord might need to cooperate with the program for you to receive assistance, and the program will pay the rental assistance to the landlord or property management company directly. In other places, if your landlord does not cooperate with the program or send in required forms, the program will pay the tenant directly. If your landlord does not cooperate with the program, ask if it’s possible for the assistance to be issued to you instead.

If you’ve already lost your home, call 2-1-1 or check Just Shelter to find out about shelters, housing providers, and support available in your community. In some states, rental assistance programs are allowing funds to be used for relocation, and you could be eligible for other benefits. Also, veterans and active duty service members have certain rights in eviction and access to additional legal counsel.

Renters may bring an attorney to represent them. Working with a housing attorney could strengthen a renter’s case. There are free legal services across the country. To apply, contact a local legal aid office. The following resources can help you find legal answers or legal representation in court:

Attorneys can help tenants raise defenses or ask the judge for more time (called requesting a continuance), or have the case sealed or dismissed. Renters should mention, regardless of whether they have an attorney, if they have a CDC declaration form or have applied for rental assistance.

In some specific locations, if someone is evicted, they may be eligible for emergency rental assistance and housing counseling services to help identify and pay the rent in a new home.

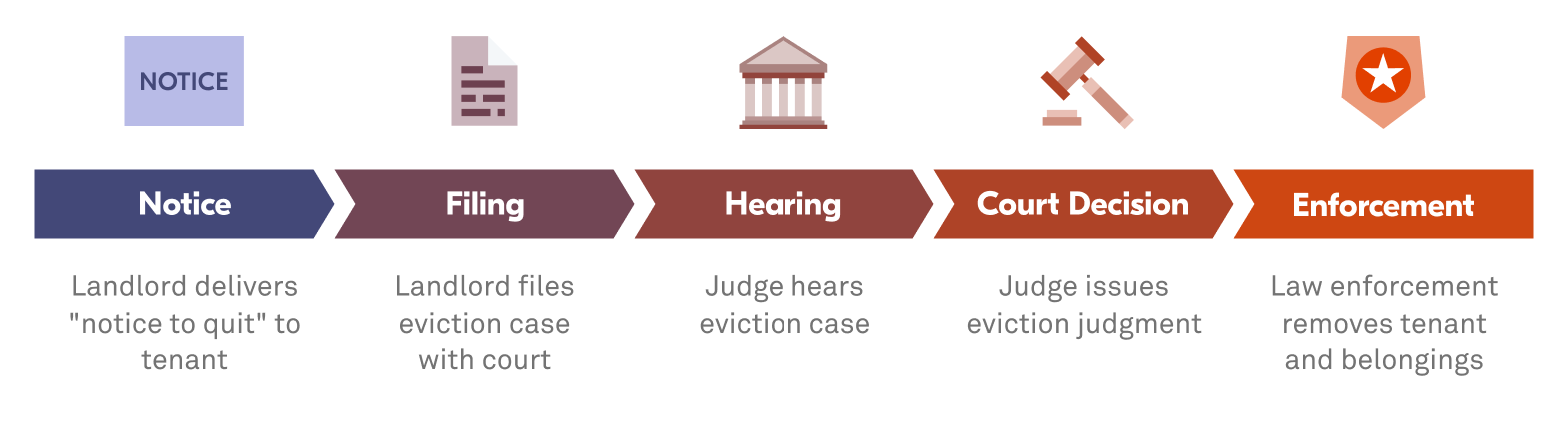

A “notice to vacate” is the first step in a process that can last weeks or even months. Most states require landlords to give you a notice of their intent to file an eviction. States have different requirements for what a notice to vacate looks like: it might be a piece of paper taped on the door or sent by certified mail, or your landlord might contact you in person or over the phone to let you know that they intend to file an eviction case against you. Depending on your state and local law, you may have a right to address any issues cited in the notice and avoid an eviction case. This is called the “right to cure.”

After delivering the notice of eviction and waiting a certain period of time, which varies by state, the landlord typically files an eviction case in court and the court serves the renter with a summons for a hearing. During the hearing, renters can raise defenses to the eviction. Defenses vary based on where you live, so it’s important to talk to a legal aid provider to find out what defenses exist in your city.

If the judge decides in favor of the landlord, the judge may issue a writ of possession. Renters can appeal the decision, leave the property, or wait until the sheriff or other party executes the writ by removing the renters’ possessions out of the unit.

Depending on the local courts, your landlord, and the status of your dispute, the eviction process might restart. If you were in an early stage of the eviction you might have to go to a court hearing. In some other cases, you might be at the end of the process and the actual execution of the eviction might happen much sooner.

Stay in touch with your landlord, with your local court, and with any organization that can provide legal assistance, to understand your particular case and how far you are in the eviction timeline. You should also apply for rental assistance in your city, county, or state program if these programs still exist where you live. Consult with your local information line to identify programs or search for programs here.

Call 2-1-1 to understand what resources are available in your area. You can find information for legal aid organizations across the country at this site.

That depends on where you live. In many states landlords are allowed by law to start eviction proceedings once the tenant is late on rent, and they’re not required to accept late or partial payments. Landlords might also be able to accept the late payment, but evict you anyway for paying late. On the other hand, in some places, landlords are required to accept a late payment that you make soon after the eviction filing, and withdraw the court case against you.

In some states and cities, there might be regulations that allow tenants to catch up in rent or create a grace period before starting an eviction court case. Contact legal services and 2-1-1 to ask about the regulations where you live. Ask whether landlords are required to accept late payments, and whether the court must dismiss your eviction case if you pay what you owe before your eviction hearing.

An eviction doesn’t directly affect the credit score, but outstanding debts could show up in your credit report, including late rent payments and late fees that are owed.

Evictions can appear though in other consumer reports and make it harder to apply for a rental unit in the future, as landlords check your history as a renter.

When an eviction case is filed, it can become a public record. This could allow a future landlord to check the eviction history of an applicant and deny an application–even if you win your case or do not leave your home. In some states, renters are allowed to seal the record of the eviction case. This could make it easier for you to find new housing in the future. In other places, some eviction cases are sealed automatically.

Check the Eviction Lab COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard to see if eviction cases from the pandemic are sealed in your state. Check with the court system in your area, or with legal services, to see if or how you can request to have your eviction case sealed. Legal services may be able to help you get your eviction case sealed, especially if you worked with legal services during your eviction hearing or if you won your case.

No matter your legal status in the United States, you are still entitled to a hearing in court, although in some specific places you might need to post a bond. According to new rules issued during the Biden administration, officers from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) can’t detain people in a courthouse.

In some cities you may also be allowed to apply for free legal assistance, and there are non-governmental organizations and pro bono (free) attorneys that provide legal support and consultation for immigrants. Many rental assistance programs also accept applications from undocumented renters.

If a landlord or an apartment manager threatens to call immigration officers to force you out, you could find help in immigrant organizations as well as some legal aid organizations. You can find a list of organizations that help and support immigrants in legal affairs here.

Renters across the United States have found strength in speaking to one another and organizing for better housing conditions, from experiences during the Great Depression, the 1970s, to today. Consider contacting your neighbors, local tenants union, and housing advocates to learn more.

You can find a list of local organizations that need your support in our sister site, Just Shelter.