March 26, 2021 marks the one year anniversary since the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) was signed into law. The large spending bill instituted a historic pause on evictions, or eviction moratorium, from March 26 until August 25, 2020. The CARES Act temporarily prevented landlords from beginning the eviction process against tenants who live in several types of federally-financed housing, though problems with enforcement allowed an unknown number of tenants who should have been protected to be evicted anyway.

As we cross this pandemic anniversary, the Eviction Lab looked back and evaluated twelve months of emergency government measures designed to keep people in their homes. In the first two weeks of May 2020, when protections were greatest, more than 24 million renters lived in states with strong eviction moratoria. Even more renters in states with weaker protections, or without any eviction-blocking orders, were protected by local eviction-prevention orders and the CARES Act. But as the pandemic wears on, policymakers across the country have declined to keep protections for renters in place.

In analyzing what happened with eviction moratoria in the last year, we can see the lifesaving options available to policymakers—as well as what happens when policymakers don’t enact housing stability policies, or opt for weaker protections instead of more inclusive anti-eviction measures.

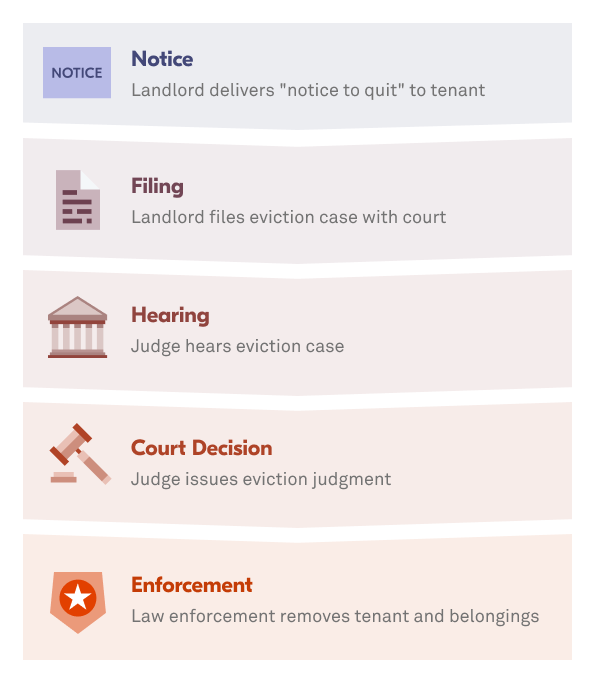

The Eviction Lab began tracking federal, state, and local moratoria on March 19, 2020. We soon found that not all moratoria offered the same protections to renters. Some moratoria, like the CARES Act, only stopped evictions for certain tenants—often those who could prove they couldn’t pay rent because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Others only stopped parts of the eviction process: for example, an order might stop the final enforcement of an eviction order, but still allow landlords to file eviction court cases. In still other places, governors, courts, and state legislatures declined to implement any pause on evictions during the pandemic.

To help our audience make sense of the different eviction moratoria, and to allow people to compare states' moratoria, the Eviction Lab and Professor Emily Benfer created the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard. The Scorecard distills thousands of orders related to eviction moratoria and other policies to support renters staying in their homes during the pandemic into a score out of 5.0 stars for every state and the District of Columbia.

In this Preliminary Analysis post, we take a first look back at the year of eviction moratoria to see when and where protections for renters were strongest and most effective. We use a 4.5 star scale to evaluate states, excluding 0.5 credit we awarded to states on the Scorecard for financial rental assistance.

State scores from the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard. Darker shading corresponds to stronger anti-eviction protection.

Thirty states and the District of Columbia already had at least one anti-eviction protection in place the week that Congress passed the CARES Act. In the early days of the pandemic, courts closed and postponed hearings in all but the most essential cases, which courts deemed did not include evictions. These eviction moratoria generally came from the courts themselves as they closed their doors. These court-closure orders covered all renters, which made their protection very inclusive, but they also created serious confusion: What happened if you already had an eviction judgment against you? If you had a court hearing date set already, would you be notified of a new date? Could landlords still file eviction cases if the court buildings were closed?

As states began to issue stay at home orders—requiring people to stay in their homes, socially distance from others, and wear masks, and closing schools and businesses—the urgency of these questions ramped up. Many governors included eviction moratoria among the public safety measures that they ordered during the pandemic. These orders were often more protective than the court orders, in that they would stop more parts of the process than only court hearings.

In Minnesota, for example, the governor’s executive order stopped landlords from issuing a notice to quit or filing to evict a tenant, paused hearings, and stopped law enforcement from carrying out evictions. This order applied to all tenants and all eviction cases except limited emergency situations. Minnesota’s governor first ordered this strong moratorium on March 16, 2020, and it is still in place as of March 29, 2021. The Eviction Lab estimated that the Minnesota moratorium, alongside financial rental assistance, prevented more than 10,000 eviction cases from being filed in Minnesota during the pandemic.

State scores from the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard. Darker shading corresponds to stronger anti-eviction protection.

State-level eviction protections peaked in the middle of May 2020. At that point, 11 states and the District of Columbia had eviction moratoria in place that were valued at 2.5 stars or above on the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard (excluding 0.5 stars for rental assistance). Policy regimes that scored at 2.5 stars or above had protections covered at least a broad swath of renters, including those who lacked documentation to prove their loss of income due to the pandemic, and blocked multiple stages of the eviction process. Most states that didn’t have such strong protections still had at least one eviction-limiting measure in place, too. On Monday, May 11, 2020, 41 states and the District of Columbia had paused at least one part of the eviction process for at least some renters.

Data from the Eviction Tracking System (ETS) show that in places with strong state or local protections in effect to prevent evictions, eviction filings dropped to a fraction of what courts saw in a normal year, and stayed low even as the pandemic continued. In places without local protections, eviction filings climbed back towards “normal” levels as the pandemic wore on.

As spring turned to summer, some state and local policymakers opted not to extend eviction moratoria. The CARES Act expired on July 25, 2020, and the extra $600 a week for unemployment benefits ended less than a week later. The first eviction cases against tenants living in properties covered by the CARES Act could be filed on August 25, 2020. Eviction Lab researchers found eviction filings skyrocketed after the CARES Act protections ended, and in the absence of strong state and local eviction moratoria.

In some instances, policymakers consciously allowed tenant protections to lapse in time with state rental assistance programs opening, like in Michigan. This strategy was not successful at preventing eviction filings for several reasons: renters need to know about and fill out often extensive paperwork to apply for rental assistance (leaving renters who aren’t in the know without recourse), application processing takes time (during which landlords might file to evict), and some landlords decline to accept payments (leaving their tenants without protection from eviction).

The lifting of eviction moratoria also coincided with a general reopening of American life outside the home in summer and fall 2020. Data from the ETS show that eviction filings went up in cities where eviction protections ended after the expiration of those orders—even if the expiration happened while a federal eviction ban was in place.

On September 5, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ordered a new federal eviction moratorium. That order is scheduled to expire on March 31, 2021, but already, how well the order protects renters varies significantly from place to place. In some parts of the country, tenants who provide a signed and filled out CDC declaration can have their cases dismissed immediately, and landlords aren’t filing as many cases as normal. In other places, landlords are filing roughly as many eviction cases now as they did before the pandemic, and tenants who provide CDC declarations still might receive eviction judgments and writs.

State scores from the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard. Darker shading corresponds to stronger anti-eviction protection.

By late fall 2020, state policymakers had ended most state-level protections, even as cases of COVID-19 rose across the country. In 2021, as we arrive at many one-year anniversaries related to the pandemic, state policymakers have not taken any new actions to stop evictions. At the federal level, President Biden extended the CDC order and Congress issued more financial assistance to renters, but have not addressed the problems with the federal CDC order that have permitted landlords to file hundreds of thousands of eviction cases.

A few states stand out for keeping their eviction moratoria in place. In Minnesota, Connecticut, and New Jersey, for example, eviction moratoria are tied to the state of emergency instead of an arbitrary deadline. Washington’s eviction moratoria is not scheduled to expire until June 30, 2021. And California, Oregon, and New York have taken steps to ensure tenants are not evicted in the future for housing debts that accrue during the pandemic.

A small number of other states stand out for implementing new moratoria in winter 2020, after earlier measures had expired. Nevada, for example, blocked eviction notices and filings from March 30, 2020 until October 15, 2020. After a two-month gap, their block on notices and filings was revived in December 2020. As of this writing, landlords in Nevada are forbidden from issuing notices to quit to or filing eviction cases against tenants who provide a signed CDC declaration.

State scores from the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard. Darker shading corresponds to stronger anti-eviction protection.

The early eviction moratoria, in spring 2020, represented unprecedented steps towards housing stability. As governors asked people in their states to stay at home, wash hands, socially distance, and mask up, it made sense to stop people from being removed from their homes.

As the crisis wore on, however, policymakers declined to continue extending the orders that kept renters housed in spring 2020. Most state and local eviction moratoria have ended, and the federal eviction moratorium is scheduled to end soon. Millions of renters can’t pay their rent, and smaller landlords are feeling the pinch, too, with some unable to keep up with mortgages and other expenses when tenants fall behind.

| CDC Order | Minnesota | Missouri | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Dates | September 4, 2020 to March 31, 2021 | March 16, 2020 until the end of Minnesota's public health emergency | No order |

| Eviction notices and filings | Permitted under order | Paused during health emergency | Ongoing during pandemic |

| Eviction hearings | Permitted under order | Paused during health emergency | Ongoing during pandemic |

| Execution of eviction orders | Paused for qualifying renters who file a declaration form with landlord | Paused during health emergency for all renters, except in emergency cases | Ongoing during pandemic |

Congress has funded billions of dollars of rental assistance payments, which will make their way to renters and landlords soon. But eviction moratoria and rental assistance are two sides of the same coin: the moratorium stabilizes the crisis by keeping tenants from being removed from their homes before help can arrive, and rental assistance—or other financial aid, like cash assistance—permanently resolves the shortfall. Rental assistance offered alone fails to reach all tenants—some won’t apply, or won’t have the necessary documentation to prove they’re eligible for help—and even qualifying tenants can be evicted while waiting for aid to work its way through all the red tape. Eviction moratoria on their own are temporary and fail to cancel or pay the debt that tenants accrue during the pandemic, leaving them stuck with that debt—and probable eviction—when the moratoria end.

For months, the United States had a federal eviction moratorium—the CDC moratorium—without financial aid, as the initial influx of rental assistance cash from the CARES Act had already been spent. Hundreds of thousands of eviction cases were filed during the CDC moratorium in the places we track on the ETS. As the United States now faces having rental assistance with no eviction moratorium, we can expect filings to spike even higher, as we did in August. The Eviction Lab will continue to catalogue the choices that American policymakers pick, and the eviction filings that are the consequence of those choices.