Millions of people lost their jobs or saw their working hours cut in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was felt especially hard by Black and Latino renters, the same group of people that had the highest rates of housing cost burden and housing insecurity before the pandemic. Policymakers had reason to be afraid about a surge in eviction cases as vulnerable tenants fell behind on rent across the country. To avoid a national crisis, federal, state, and local governments issued an array of temporary eviction moratoria and renter-supportive measures.

In an article published in Housing Policy Debate, we describe and analyze the unprecedented eviction prevention housing policies enacted at the state level in response to COVID-19. Over the first year of the pandemic, 43 states and Washington, D.C. instituted some form of eviction moratorium, but those protections worked very differently from state to state.

Consider the situation of a tenant behind on rent in one of three Western states on April 30, 2020. If the renter was in Washington, their landlord could not serve them with notice of intent to file for eviction, much less file the case with the courts. If they were in Idaho, an eviction case could be filed, but no hearing would be held. But if they were in Wyoming, the eviction process could proceed as normal.

To better understand these policies and how they left some renters with far more protection than others, we reviewed over 1,500 orders put in place across the country between March 13, 2020 and March 13, 2021. We’ve released a publicly available dataset that describes the content of these orders in detail through March 2022. In the article, we focus just on the first year of the pandemic and provide a high-level overview of what we found, identifying five key dimensions along which policies varied.

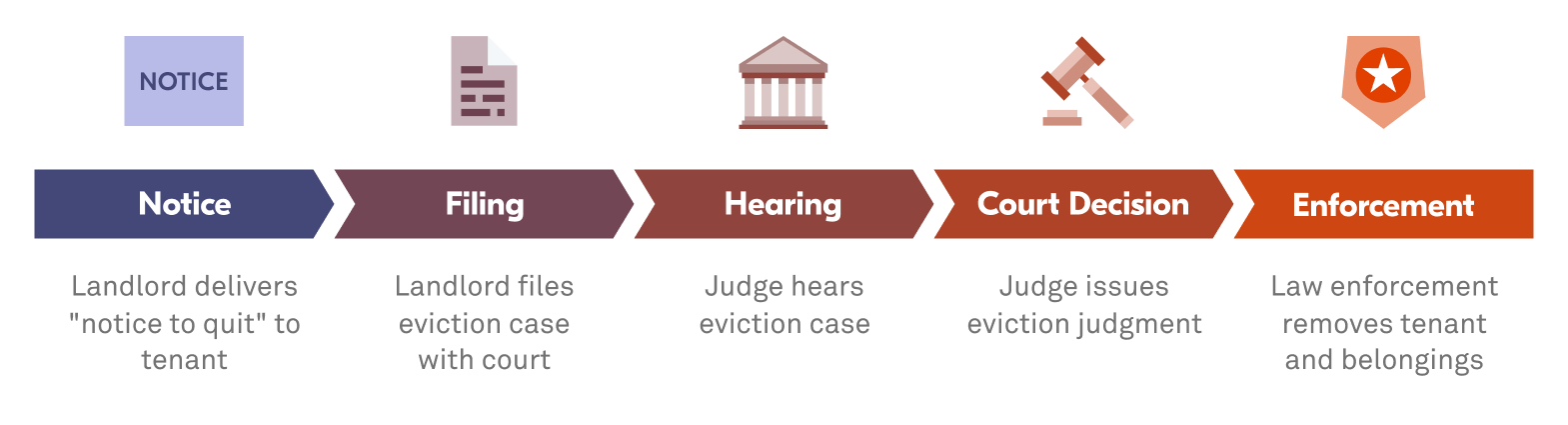

while most states halted parts of the eviction process, only a handful froze evictions completely. Generally, the eviction process can be broken down into five stages: the landlord provides notice to their tenant that they intend to evict them; the landlord files an eviction case with the court; the court holds a hearing; the court issues a judgment; and law enforcement executes the eviction.

Across the states that ever established an eviction moratorium, the most common protection was to freeze that final stage of the process—law enforcement execution of the eviction—which was halted 70% of the time. Court hearings were suspended by 68% of moratoria and eviction filings were stopped by 54% of moratoria. Only four states—Hawaii, North Carolina, Nevada, and Massachusetts—froze all stages at some point.

some moratoria lasted a lot longer than others. The earliest eviction moratorium went into effect on March 13, 2020, and some remained in effect as of March 13, 2021. The typical length of a moratorium was 144 days. The longest moratorium during the first year of the pandemic was issued by the Washington, D.C. Superior Court and later extended by the DC Council. It went into effect on March 15, 2020 and was still in place at the end of the study period (363 days). The shortest moratorium was issued by the North Dakota State Supreme Court and was in effect for only 27 days. In Figure 1 we plot the presence and overall duration of protections in each state and D.C.1

Shading represents total number of days of protection for each state.

some branches of government were more likely than others to establish eviction protections. The vast majority of eviction moratoria were implemented by governors and courts. Indeed, only seven moratoria were issued by legislative bodies. In many states, more than one actor issued an eviction prevention policy, meaning that a combination of measures implemented by multiple actors created a patchwork state-level moratorium.

actors justified moratoria on public health grounds or based on their concern about the economic impact of the pandemic affecting tenants’ ability to pay rent. In many cases, they used both reasons. Public health-based justifications often pointed to the ways in which eviction increased individual and community vulnerability to COVID-19. By contrast, the economic rationale suggested that the state should ensure that residents did not lose their homes due to an economic catastrophe beyond their individual control. In establishing eviction moratoria, six states cited only the public health justification, five only the economic reason, and 21 states and Washington, D.C. cited both.

we find that most moratoria restricted eviction protections to certain renters or certain types of eviction cases. There were two particularly common forms of restriction. The first limited protections to those who could demonstrate a COVID-19 hardship like job or wage loss. The second halted eviction cases brought for nonpayment of rent but allowed other cases, like when the landlord argued that the tenant created a nuisance or public hazard or had stayed beyond the lease term. Initially, 34 states and Washington, D.C. applied moratoria to all evictions without eligibility restrictions.2 Over time, nearly half of these jurisdictions limited protections to nonpayment of rent eviction, demonstration of COVID-19 hardship, or both.

In addition to moratoria, we also describe the different ways that states adopted and implemented the two federal eviction moratoria (the first enacted as part of the CARES Act, the second issued by the CDC). We also show how some states put in place additional renter-supportive measures, such as financial assistance to tenants, utility shutoff moratoria, utility reconnection, bans on late fees and rent raises, grace periods to pay rent, measures sealing eviction records, and bans on landlords reporting past-due rent to credit bureaus.

The rich description of state-level eviction prevention policies provided in the article is critical in fully understanding how policy-makers responded to the pandemic. It also allows us to explore the conditions that fostered more or less active response and what effects these policies had in practice. In the article, we lay out a pair of exploratory analyses that demonstrate how these data could be used moving forward.

First, we show that states began to roll back protections—or restrict the original protections that they offered—well before the pandemic was contained. Indeed, in most cases, protections were lifted even as case rates were increasing. It was very rare for state policymakers to expand protections over time, despite clear public health risks. In the vast majority of places where moratoria were enacted, the highest COVID-19 infection rates were recorded after renter protections were lifted or weakened.

In Indiana, for example, the average COVID-19 infection rate during the period in which the state halted the filing of eviction cases (March 19 to August 15, 2020) was 7.9 per 100,000. Four months later, on December 3, 2020, infections in the state spiked to 102.5 per 100,000, yet no new protections were afforded to renters. State governments often cited public health concerns to justify establishing moratoria, but we found little to no evidence that this mattered when lifting protections.

Second, we explore how eviction moratoria had an impact in the number of eviction case filings. To do so, we conduct a regression analysis using eviction filing data gathered by the Eviction Lab, the Legal Services Corporation, and the Metro Atlanta Evictions Data Collective. We demonstrate that eviction case filings were lower when moratoria were in place, and in particular that policies that halted earlier stages of the eviction process had a significant effect in reducing eviction filing rates. This finding is both intuitive and fundamentally encouraging: policies specifically designed to shield households from the threat of displacement appear to have worked.

The COVID-19 pandemic is the first time that eviction moratoria have been established on a nationwide scale. It is essential that we fully understand the measures that were implemented in response to the pandemic. Doing so ensures that we know what tools are available the next time we face an emergency, and so that we can evaluate which of these policies work best. The framework that we lay out here provides researchers and practitioners alike with the tools to advance, evaluate, and refine comprehensive renter protection strategies. Understanding and improving these tools serves to safeguard the communities most impacted by public health or other emergencies from housing loss and associated harms.